Young Researchers’ 2nd Indo-Persian Workshop

23-24 mai 2024

La deuxième édition de l’atelier des jeunes chercheurs en études indo-persanes s’est tenue le 23 et le 24 mai 2024 à l’EHESS Marseille, au campus de la Vieille Charité. Le thème retenu était celui de l’écriture dans la culture indo-persane. Les disciplines couvertes ont été nombreuses puisque les communications présentées ont traité tout autant de philologie que de paléographie, de codicologie, sans oublier l’histoire de l’art (de la calligraphie notamment) et de l’architecture.

Les deux journées ont été organisées par Raffaello Diani (EHESS, CESAH) et Victor Baptiste (EPHE-PSL, GREI). Cet événement a été financé par l’EHESS, le CESAH (UMR 8077), le centre CeRCLEs (EHESS), l’ED 472 de l’EPHE-PSL et le GREI (EA 2120). Outre les organisateurs, plusieurs des participants ont pu se rendre sur place, notamment grâce à l’aide financière aimablement apportée par le GREI et l’EPHE-PSL. Mme Ayelet Kotler (Université de Leyde), Mme Annalisa Bocchetti (Université de Gand), Mme Rachel Cochran (Université de Caroline du Nord) ainsi que Victor Baptiste ont présenté leurs communications à Marseille alors que Mme Mahdieh Khajeh Piri (Aga Khan Development Network), M. Kartik Maini (Université de Chicago), M. Shakir ul-Hasan (Université de Delhi) et M. Mohammad Rehmatullah (Jamia Millia Islamia) se sont joints à l’atelier à distance, depuis l’Inde et les États-Unis. Mme Girija Joshi (CESAH) a présenté sa communication à distance depuis Paris.

Les sessions ont été présidées par plusieurs professeurs qui ont aimablement accepté de participer aux deux journées. Mme Eleonora Canepari (EHESS) et Mme Françoise Nalini Delvoye (EPHE-PSL) ont présidé les deux sessions du 23 mai alors que M. Chander Shekhar (Université de Delhi) et M. Fabrizio Speziale (EHESS) ont présidé le 24 mai.

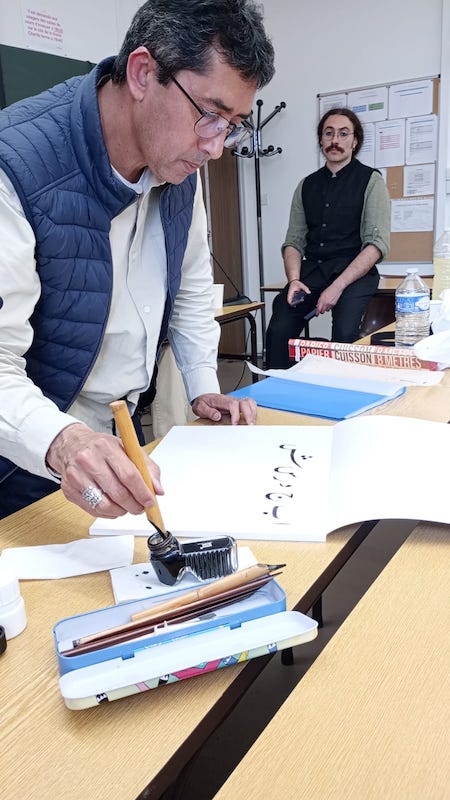

L’atelier s’est conclu par une démonstration participative de calligraphie perso-ourdoue exécutée par M. Bédar Abbas (Chargé de collection pour les domaines ourdou, pendjabi et pachto à la BULAC) qui a gentiment accepté de faire le déplacement jusqu’à Marseille pour présenter aux participants sur place et en ligne quelques-unes des techniques calligraphiques encore en usage de nos jours en Asie du Sud. L’atelier a donné lieu à de nombreux échanges scientifiques enrichissants entre les participants et a permis aux jeunes chercheurs de faire connaissance à travers plusieurs continents.

Programme détaillé et résumés des communications

Programme détaillé

Jeudi 23 mai

Matin, présidente de session : Mme Eleonora Canepari (EHESS)

- 10h15 : Shakir-ul Hasan, “Paper, Literacy and Economy of Bookmaking in Kashmir c. 1500-1900”

- 11h : Mahdieh Piri, “An Epigraphical Journey to the Qutb Shahi Necropolis”

- 12h : Victor Baptiste, “The practice of the Persian headings in Avadhī manuscripts”

Après-midi, présidente de session : Mme Françoise ‘Nalini’ Delvoye (EPHE)

- 14h30 : Mohd Rehmatullah, “Vernacular Bhakti Writings in Persianate India: Exploring the ‘Muslim language’ of the Pranāmī Texts of the 17th century.”

- 15h15 : Annalisa Bocchetti, “The Art of Rewriting the Mystical : An Introduction to a 19th century Manuscript of the Qiṣṣah-i Rāja Kunvar Sen o Rānī Citrāvalī

- 16h : Ayelet Kotler, “The Persian Translation of the Śivapuraṇa and 18th century North Indian Śaivism.”

- 17h: Kartik Maini, “Writing, Imagery, and the Monastic Everyday: The Social Lives of Premodern Manuscripts”

Vendredi 24 mai

Session du matin, président de séance : M. Chander Shekhar (Université de Delhi)

- 10h15 : Girija Joshi, “Between Chronicler and Archivist: Munshi Inayatullah and the Tarikh-i Riyasat-i Kalsia.”

- 12h : Rachel Cochran, “Tarikh-i Qipchaq Khani: An 18th century Universal History from Lahore”

Session de l’après-midi, président de séance : M. Fabrizio Speziale (EHESS)

- Atelier de calligraphie animé par M. Bédar Abbas

Paper Literacy and Economy of Bookmaking in Kashmir c.1500-1900, Shakir-ul Hassan

Historiographical purview of the early modern papermaking and bookmaking in South Asia has not been adequately studied. Relatively recent art surveys vis-à-vis Kashmir under aegis of ‘visual turn’ concentrate on skillful conceptions of sculptors, shawl-makers, metalworkers and structural elegance of pietistic buildings while the oft-neglected Islamic bookmaking techniques await specialized study. Counter to the contentions of professional orthodoxy, this study marks a big shift in tracing the economy of book vis-à-vis political and cultural matrix in Kashmir. Shawls and paper formed commercial products of Kashmir, yet, the former has received immense historical devotion, of course, it being component in robes of honour (ḵẖilʻat). This essay reclaims historical trajectory of paper-industry (ḵẖāgaz-sāzi) and manuscript culture (mas’udāt) in Kashmir c.1500-1900 since the gradual diffusion of perdurable paper as writing-material proved instrumental in adding seminal agency to literate mentality. It effected the growth of textual-cum-scribal communities viz., khatāt, ḵẖushnavīsiyan, ganāie, munshi and kārkun in urban cities without displacing pre-existent forms of birchbark documentation (bhojapatra). It attends to economy of bookmaking in Kashmir that honed within Timurid visual vocabulary and substantive essence of illustrated bookmaking operations as this craft rolled into commercial mass-production by late eighteenth century.

Textual communities, Timurid An Epigraphical Journey to Qutb Shahi Necropolis, Mahdieh Khajeh Piri

The epigraphically documented tombs are an essential feature of the Qutb Shahi Necropolis and are the most extensive and the best epigraphically documented in India. The Qutb Shahi sultans were of the Shia religion. They displayed their religious beliefs by carving beautiful inscriptions on their tombstones so uniquely that we do not see their examples on tombstones in any other part of the Deccan region. This study is inspired from examining inscriptions of the graves of Qutb Shahi Necropolis, located in Hyderabad, India. The Qutb Shahi dynasty ruled from the Golconda fortification between 1512 and 1687 AD for over 171 years before Aurangzeb conquered Deccan in 1687 AD. They built a dynastic necropolis in a peaceful corner north of the Golconda fort, spread over 106 acres of land. The site has over 100 structures, including mausoleums, funerary mosques, hammam, garden structures, and step-wells. Seven out of eight Qutb Shahi Sultans, their immediate family, and the officials who served them, including Hakims and concubines, are buried at the site. Overall, 193 graves made of black basalt, granite, and lime finish survive at the site; 38 graves have inscriptions, and 14 of these graves bear the names of the deceased and their date of death. They combined Quranic verses, Shahada (declaration of faith), and invocations to fourteen Infallibles (Prophet Mohammad, Fatima, and 12 Imams) to portray Qutb Shahi Sultans as a propagator of Twelver Shii doctrine and protector of Sharia. The art of inscription writing is one of the most important historical and artistic elements of the Qutb Shahi Necropolis. It will be examined on 38 out of 193 graves with Arabic and Persian inscriptions. In this article, I shall examine the following topics related to the inscriptions: (i) The Shiite beliefs of the Qutb Shahi Sultans and the manifestation of these beliefs in the epigraphic program of the inscriptions. (ii) The type of scripts used in the inscriptions and the investigation of their development from the construction of the tomb of the founder of this dynasty Sultan Quli Qutb al –Mulk (d.1543) until the construction of the last unfinished tomb of Fatima Khanum, the daughter of Sultan Abdullah Qutb Shah in 1087. (iii). Analysis of the form and shape of the graves. (iv) The study of the conscious collaboration of patrons and artists that is reflected on epigraphic program.

The Practise of the Persian headings in Avadhī manuscripts, Victor Baptiste

A number of manuscripts of Avadhī Pemakathās (“romances”) written in the Perso-Arabic script contain headings written in Persian, inserted before each stanza (dohā-caupāī), which describe the content of the coming verses. This is a feature found both in the ancient illustrated manuscripts of Candāyān (15th -16th century) and in some of the later manuscripts of the 18th century. In this presentation, I will address the technical terminology problems that we are facing to describe these elements with the classical Persian codicological vocabulary (sar-faṣl, sarʿunvān, sar-khat̤, surkhī?) in order to reflect on the unique function that these Persian descriptions had for their readership. I will then describe the recurring components of these headings and analyse the scribal practises involved (graphical elements, conventions, scripts used). I will focus on three manuscripts, two 15th and 16th century manuscripts of Candāyān (Manchester, Berlin) and one 18th century manuscript of Padmāvat (Paris) in order to establish a typology of the headings based on their contents. This will allow a reflection to unroll on the multilingual vernacular and persianate reading practises of Early Modern South Asia. Indeed, in this presentation, I will attempt to demonstrate that these headings were meant to lead the gaze of a highly literate readership, capable of identifying literary tropes, symbols and new poetic meanings across different languages. The intricate nature of the Pemakathās, written in a Neo-Indo-Aryan language, but following many of the conventions of the Persian masnavī, is indeed an exceptional material for inter-lingual and inter-literary meditations focusing on poetic creativity (khayāl-pardāzī) and literary meaning (maʿnī-afrīnī). The headings were, as a result, not only here to help the reader in identifying the elements and interesting tropes of the vernacular text but were also acting like a first layer of interpretation and intertextual analysis.

Vernacular Bhakti Writings in Persianate India: Exploring the ‘Muslim Language’ of the Pranami Texts of the Seventeenth Century, Mohd Rehmatullah

The paper seeks to address the issue of the presence of ‘Muslim language’ in the large corpus of Pranami vernacular devotional and hagiographic literature of the seventeenth century. Those critical of the beliefs and practices of the Pranami community use the term ‘Muslim language’ to imply the excessive influence of Islam on the Pranami religious preachers, particularly Prannath, the seventeenth-century founder of this Bhakti-based devotional community, and also the preponderance of Persian and Arabic words in the Pranami devotional and hagiographic texts. This paper seeks to argue that it was a common practice among many Mughal-period Bhakti poets and hagiographers to draw upon Islamic ideas, particularly Shia millenarianism, and also upon Arabic and Persian languages and literary cultures. These cultural and literary interactions did not distract the Pranamis and other Bhakti-based communities from their vernacular and devotional moorings. Based on an exploration of a large number of Pranami vernacular texts of the seventeenth century, including Kulzam Swaroop and Bitak, the research paper is also intended to make a further contribution to the understanding of the burgeoning field of the formation of early modern Indian Hindi literary cultures and their historical context. The paper also addresses the issues of readership of these literary texts and the audience of the storytellers. The paper makes an attempt to answer the question of whether these texts were intended solely for the Pranami followers or were also targeted at a larger audience and social groups in the Indo-Persian world within the Mughal Empire. In undertaking an exercise of this nature, the two-way interaction between orality and literacy assumes particular significance, which has been touched upon in this paper. Two major literary genres in the Pranami literary traditions are Bani and Bitak, both of which have their roots in the North Indian vernacular literary traditions of the period. The subject matter of this paper is how Pran Nath and the Pranami storytellers used these indigenous forms to put forward millenarian claims derived from Islamic traditions.

The Art of Rewriting the Mystical: An Introduction to a Nineteenth-century Manuscript of the Qiṣṣah-i Rāja Kunvar Sen o Rānī Citrāvalī, Annalisa Bocchetti

With this contribution, I aim to shed light on an unexplored Urdu manuscript from early nineteenth-century North India, namely the Qiṣṣah-i Rāja Kunvar Sen o Rānī Citrāvalī (‘Story of King Kunvar Sen and Queen Citrāvalī’). As a result of my current research, I contend that this manuscript represents an Urdu retelling (dar naz̤m-e-Urdū) of the Citrāvalī, a Sufi premkathā composed in Avadhī by Sheikh Usmān (1613 CE). In keeping with tradition, Usmān’s mystical text provides a fascinating allegory of Creation and the seeker’s mystical journey through the narration of the love story of Prince Sujān and Princess Citrāvalī. Throughout the text, symbolic artistic and painting imagery is used to convey complex Sufi ideas of ontology and metaphysics. No translations or retellings of Usmān’s poem have surfaced so far, except this anonymous qiṣṣah that appears two centuries later, listed in the Catalogue of Hindi, Punjabi and Hindustani Manuscripts (Blumhardt 1899). Although the text is written in Urdu, scattered Persian interpolations can be found within and around the text, indicative of contemporary writing practices. The anonymous author, whose manuscript appears to be commissioned by Colonel George William Hamilton (1807-1868), states that the story is popular in India and is included in the repertoire of storytellers/historians (muʼarriḵẖ) (folio 24). The adapted text retains the vernacular artistic semantics and painting symbolism of the premkathā (1613 CE) but presents them in a language and narrative form for an Urdu-speaking public. Considering the importance of historicizing the source, I shall first describe the cultural and literary legacy of the Urdu manuscript within Islamicate India’s transregional storytelling networks that allowed texts to travel across scripts, languages, and genres. Therefore, I propose that the Sufi story was part of the repertoire of storytellers flowing through the multilingual manuscript tradition of India. As the story of Citrāvalī is adapted into the qiṣṣah genre, the paper will explore questions related to assessing the manuscript’s socio-historical nature and its reception within Indo-Muslim milieus. Thus, using information gathered from the text’s body and margins, I intend to gain insight into the identity of agents involved in the revival of the story and the changing readership who could engage with the adapted text, appealing to their tastes, models, and expectations. Introducing selected parts of the Urdu manuscript for the first time, I will illustrate how the text shows the influence of the Urdu and Persian reading culture of Islamicate India.

The Persian Translation of Śivapurāṇa and Eighteenth-Century North Indian Śaivism, Ayelet Kotler

Our knowledge of the historical circumstances under which people have composed, read, copied, and translated Sanskrit puranic texts has many gaps. This is, as they say, not a bug, but a feature of puranic discourse: two fundamental characteristics of purāṇas are their claim of primordiality and sacredness on the one hand, and the process of ‘composition-in-transmission’ that produced them, on the other. Yet, despite the puranic composers’ best efforts to disguise their historicity, cultural-historical research that is firmly rooted in rigorous philological work on purāṇas is possible, as has been shown by the ongoing reconstruction of the different stages of the transmission of the Skandapurāṇa in Sanskrit. One productive and perhaps surprising place to look at when studying the transmission, transformation, and reception of purāṇas is the corpus of Persian purāṇa translations from the eighteenth century. It is productive because studying translations is always a crucial component of any attempt to map and understand the transmission and reception of a textual tradition. It might be somewhat surprising, though, to examine Persian translations to shed light on the transmission history of purāṇas: as if the “composition-in-transmission” of purāṇas does not make life hard enough for scholars when it comes to determining with any accuracy the historical circumstances of any given text, Persian translations of Sanskrit literature, too, are notorious for being silent on their sources. Without the painstaking job of a close comparative reading of a range of Sanskrit manuscripts and recensions against the Persian translation, it is impossible to pinpoint the sources with which Persian translators in early modern South Asia worked. Not only that, but Persian translators of narrative literature in early modern South Asia are also known for not considering faithfulness in translation a guiding literary ideal. Yet, studying Persian purāṇas can illuminate not only matters of textual transmission and criticism, but also severely understudied cultural-historical aspects of Persian translations of Sanskrit literature. The strong association between Persian and Islam in scholarship on early modern South Asia has often led researchers to examine Sanskrit-Persian translations primarily as sites of religious encounters between Hinduism and Islam as well as a tool of Mughal political self-fashioning. Persian translations that were produced outside the Mughal court, like those of Sanskrit purāṇas, by Persianized Hindu scribes, have thus been badly neglected. This paper explores the Persian translation of the Śivapurāṇa, composed by Kishan Singh ‘Nashāṭ’ of Sialkot, probably in 1730, and entitled Shiv Puran. Exploring the Persian Shiv Puran and the work of Nashāṭ more broadly is extremely productive not only because it is a valuable source in reconstructing the life and education of Persianized Hindu scribes in the early eighteenth century, thus complementing existing scholarship on “the world of the munshi”. It can also uniquely shed light on aspects of the social history of lay Śaiva communities in northern South Asia, the ways in which early modern readers understood and used purāṇas, and the muddled textual transmission of the Śivapurāṇa in Sanskrit and beyond.

Writing, Imagery, and the Monastic Everyday: The Social Lives of Premodern Manuscripts, Kartik Maini

Early modernity was, for Indic traditions, a period of intense institutionalization through monasteries or seminaries (maṭhas) modeled after Sufi khānqāhs and ribāṭs. The maṭha, we know, was a space of brisk textuality where literary, scholastic, and philosophical canons were being reimagined, and the charismatic authority of saintly men & women slowly forged. This paper is grounded in one such tradition – the Rāmdāsī sampradāya of Samarth Rāmdās (c. 1608-1682) – and the textual ephemera of its many maṭhas in the Deccan. I aim to use manuscripts produced at Rāmdāsī maṭhas in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries to address questions of social history. Writing and imagery, I argue, helped the maṭhas’ inhabitants find their institutional bearings in a deeply uncertain world marked by internecine warfare, sectarian rivalries, and the vicissitudes of state-sponsored scribal labor. Early modern Rāmdāsīs confronted the precarity of their times through everyday devotional labors that helped bring the monastery into being. Such labors were primarily textual, ranging from the kind of writing that aided self-cultivation (e.g., copying Rāmdās’ utterances by hand) to ordinary acts of recording transactions, gifts, and deaths. I examine three registers of evidence – the maṭha’s inventorial ledgers, its images of worship, and the occultic designs or devices (yantras) that curiously adorn much of its textual record – taking, in each case, their deceptive mundanity seriously. Bringing diverse languages (Marathi, Hindi/bhāṣā, Sanskrit, Persian), scripts, and sensibilities together, Rāmdāsī scribes yoked writing’s workaday fluencies to transcendental ends. In so doing, they opened devotional religion (bhakti) to the transformative powers of the written word and the drawn image.

Between Chronicler and Archivist: Munshi Inayatulla and the Tarikh-i Riyasat-i Kalsia, Girija Joshi

This paper offers a reflection upon scribal practices in nineteenth- into early-twentieth century Panjab, as they relate to Persianate histories (tawarikh) from this period. Such works in Persian and Urdu had begun increasingly to be commissioned by various Panjabi riyasats and their dependents (namak-khwaran) from the early nineteenth century, as a means of undergirding their territorial claims vis-à-vis the expanding empires of Maharaja Ranjit Singh and the English East India Company (Dhavan 2007). While some of these works appeared as finely-produced courtly books, a significant number seem to have been family histories kept in private possession, that minutely record the evolving relations between Panjabi riyasati households, the networks of their relations (rishtedaran), and the lands that they controlled (patti). Such works continued to be produced even after the Company’s conquest of trans-Satlaj Panjab in 1849, partly under colonial encouragement, but also out of their own initiative as savvy precautions against attempts by rivals, dependents, or the British to place claims on their territories. This paper samples a handful of texts from across this spectrum of riyasati lineage histories, before focusing upon one particular account, the Tarikh-i riyasat-i Kalsia (c. 1908), written by a certain Munshi Inayatulla in simple Urdu. This lengthy and detailed history of the Kalsia state comprises a chronicle of the different battles fought and won by its rulers, as well as a number of detailed sketches of the lineages (khandan) of the subordinate relations that had historically served the Kalsia sardars (referred to by Inayatulla as ‘tazkiras’). It also contains extensive marginal notes, numerous genealogies (shajara-nasab), copies of some significant orders issued by the colonial and Kalsia authorities, and of speeches given by the sardars. As such, the text is as much a chronicle (tarikh) as it is an archive of the affairs of the extended Kalsia household, an archive with parallels to those of older vintage maintained by powerful landholding families in other regions (Chatterjee 2020; Thelen 2021). Through a consideration of the Tarikh as narrative and artefact, this paper reflects upon the scribal practices that the riyasati and colonial contexts of nineteenth-century Panjab fostered. On the one hand, the scribe emerges as archivist and accountant, keeping a watchful eye over the affairs of his patrons at a time of consistent threat to their wealth and sovereignty. He is an information-gatherer who combines intimate knowledge about marriages, adoptions, and illicit relations, with a detailed grasp of the royal fisc, lands, and tributaries. To a lesser extent, he also fulfils the role of a panegyrist, depicting his patrons in a flattering and heroic light in idioms drawn from Persian mythology. In each of these roles, he was something of a novelty in Panjab, many of whose myriad riyasats had emerged only in the late-eighteenth century, and had begun adopting written courtly and administrative records only in the nineteenth. It is this transition to a regime of careful written documentation, and of political sovereignty beyond the Sikh Khalsa, that Munshi Inayatulla’s Tarikh allows us to trace.

The Tarikh-i Qipchaq Khani (c. 1724) of Khwajam Quli Beg Balkhi, Rachel Cochran

This paper examines Khwajam Quli Beg Balkhi’s two volume manuscript Tarikh-i Qipchaq Khani (c. 1724) held at the Bodleian Library in Oxford. This “peri-court” history was produced on the periphery of the Mughal empire in Abd al-Samad Khan’s de-facto independent Lahore. Balkhi had served the Ashtarkhanid court in Balkh before he fled the area, was kidnapped, and eventually settled in Lahore. Through an analysis of Tarikh-i Qipchaq Khani’s contents, this paper examines how Balkhi’s manuscript both drew from and reworked the tradition of Persian universal history writing, reflected in texts such as Rawzat al-Safa and Habib al-Siyar, which served as popular models for later Indo-Persian historians. It indexes the contents of Tarikh-i Qipchaq Khani and examines specific features of its introduction, conclusion, and colophon, including biographical elements. This study will also include a comparison of these elements with the structures of other paradigmatic early-modern universal histories. Particularly, it will examine Balkhi’s portrayal of Kayumars, the mythical Persian king, considering Sholeh Quinn’s recent comparative study of Kayumars in early modern Persian universal histories. This paper also discusses the circulation and scribal details of the extant copy of Tarikh-i Qipchaq Khani. Through a preliminary survey of other manuscripts produced in Hindustan during this period that similarly dealt with the history of Mawarannahr, this paper points to a growing interest in the region and its rebellions in the early 18th century. In particular, Tarikh-i Qipchaq Khani contains an account of the ‘Afghan’ Mir Wais’ 1708 rebellion against Safavid rule in Qandahar. The basic contours of this account match accounts given in several other manuscripts produced in Hindustan throughout the 18th century, including the manuscript Mirat-i Waridat (c.1736) authored by ‘Warid’. Through examination of the colophon and selected contents of Mirat-i Waridat, the paper discusses the discrepancies between the manuscript held at Salar Jung Library in Hyderabad and other versions of this text and considers the possibility that Balkhi’s work may have circulated in the Deccan. Finally, by analyzing the data contained in Tarikh-i Qipchaq Khani, this paper also makes the case that Balkhi authored the previously considered anonymous manuscript, the Tarikh-i Shaybani Khan, held at al-Beruni Library in Tashkent. Through examination of these topics, this paper aims to shed light on a little-known IndoPersian manuscript that reveals transformations in early 18th century Persian historiography and demonstrates the challenges posed by the separate area studies silos of Central Asia, Iran, and South Asia for the study of Persian writing in India.